Without planning it, I’ve fallen into an annual custom of watching Errol Morris’s memorable documentary, The Fog of War.

On reflection, I would suggest that anyone with leadership or management responsibilities add this film to their must-see list. At the least, each appointee of every new presidential administration might be urged to sit and think their way through this chastening catalog of how one person of great energy and ability can make an extraordinary, tragic difference.

The film examines the life and work of Robert McNamara, architect of the Vietnam War.

Historical Context

Morris is notably effective in presenting the historical context for McNamara’s career. McNamara’s earliest memories include Armistice Day in 1918, marking the emergence of the United States to the heights of international power. He participated in the Second World War, lending his prodigious talent for statistics to assist in the management of strategic bombing against Germany and Japan. After the war, he became part of the surging meritocracy that would transform corporate America. McNamara rose to the summit of influence at the theretofore cocooned Ford Motor Company, ultimately selected as president by Henry Ford II.

From there it was a quick, seemingly seamless move into John Kennedy’s New Frontier. McNamara, a nominal Republican, was offered Treasury or Defense. The ‘Whiz Kid’ felt he was unqualified for Treasury—but was comfortable assuming a life-and-death decision-making role in the Pentagon.

Kennedy was likely attracted by McNamara’s cocksure ways. They were both of a new generation in Washington, marked by their youthful service in World War II. Each may well have felt he understood lessons lost on his predecessors. JFK had led in combat; Ike had not. McNamara had analyzed the actual effects of strategic bombing; generals like Curtis LeMay were able to improve their performance with McNamara’s insights.

McNamara appeared to be an inspired choice to impose civilian control over the sprawling “military-industrial complex.” Perhaps some narrow-minded certainty and even some lack of historical knowledge was required in order to assume the task. It was fitting that a portrait of the brilliant, doomed first secretary of defense, James Forrestal, hung prominently behind Secretary McNamara’s desk, inviting comparison.

Fate would soon enough cast McNamara into an unfamiliar, less congenial role: warlord.

Warlord of the Spreadsheets

For this, McNamara was manifestly unprepared and ill-suited. As he later acknowledged, he entered the Pentagon with little knowledge of history—and, more importantly, he did not act to fill the gap. He appeared oblivious to the need for self-reflection as he rationalized the escalating Kennedy-Johnson administration involvement in Vietnam.

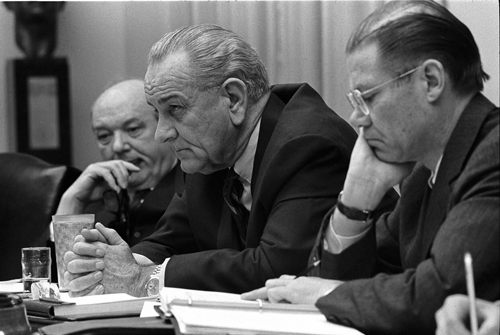

One of the chilling scenes of The Fog of War is McNamara’s farewell from the Department of Defense in early 1968. He is moved to the point of tears by the praise of President Johnson. Johnson, who appears notably less emotionally involved in the moment, has presented him with a Medal of Freedom. Soon enough, McNamara would be ensconced at the World Bank.

Was Johnson’s patronage calculated to maintain McNamara’s silence about his evolving views of the Vietnam war?

Even in his dotage, McNamara sought to evade accountability for his stewardship. He spoke of serving the president. What is striking is how little he spoke of his own, independent obligation of judgment. He certainly did not indicate publicly that he was mindful of his duty to serve the American people, or the nation itself as an ongoing, historic enterprise.

McNamara sought to bring analytical rigor to public and private bureaucracies. Along the way, he seemed tragically prone to enabling organizations to move in service of statistics, rather than having statistics put to the service of the organizations’ visions and missions.

Personal Character, Public Consequences

The technocrat who would not look to the past for perspective was unable to summon a vision of the future for guidance and inspiration. As the Johnson tapes memorialize, the automaton defense secretary was unable to steel himself to share the truth, as he saw it, with the president. Young Americans whom McNamara sent to Vietnam routinely exhibited more courage than the “brilliant” Secretary of Defense himself.

That a man of such parts as McNamara could fail so spectacularly should be a warning to everyone.

Had McNamara had a more expansive view of whom he was serving, might history have been different?

Americans often discuss how we can best avoid becoming entangled in future “Vietnams.” Perhaps we should ask how we can avoid having our nation’s destiny enmeshed in such failures of leadership, management, imagination, ethics, and service as distinguish Robert S. McNamara’s tragic career.