In a time when public discourse is generally at an objectively low standard, we’ve had several recent reminders of the power of words.

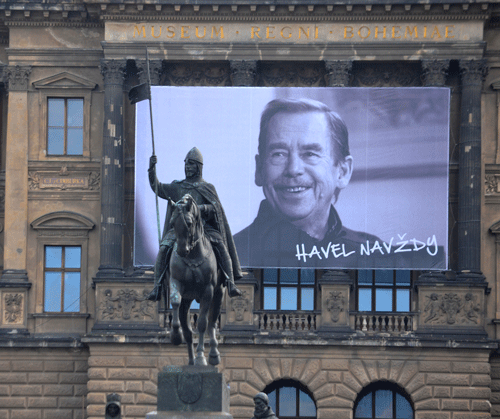

Vaclav Havel was one of the handful of world leaders who undermined the theoretical basis for communism, helping prompt the peaceful dissolution of the Soviet Union’s empire in the historic year, 1989.

Havel was a playwright who fostered the spiritual climate that emboldened his people to recognize the reality of what was before them. In turn, he encouraged them to find the power that could come from their acting as one.

As we have been reminded in the aftermath of his death, Havel was more than merely a politician who used words skilfully. Instead, he was a man of words who for whom political action was yet another tool for change.

The death of the journalist Christopher Hitchens also prompted an outsized outpouring. Can one recall a comparable reaction to the loss of another journalist in recent times?

Hitchens is rightly recalled as one of the best–perhaps the best–essayist of his time. Sometimes understandably lost amid reaction to his contrarian provocations, he had also thought deeply about the role of writers in culture and politics. One of his lesser known books is instructive: Unacknowledged Legislation: Writes in the Public Square.

Hitchens’ title is derived from Percy Bysshe Shelley:

Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.

The profound influence of one bookish public servant has long been recognized; now it is brilliantly explained. John Lewis Gaddis has produced a memorable new book on the extraordinary career and contributions of George Kennan.

George F. Kennan: An American Life explores how Kennan provided the intellectual framework within which the United States debated and implemented its Cold War strategy. That strategy, known as “containment,” would have America regard the Soviet Union more as an adversary in a competition than an enemy in a war. Kennan’s approach was predicated on his informed sense that the most effective, as well as most moral, approach would be to isolate the Soviet Union until such time as its internal contradictions might bring it down.

Gaddis asks and answers an important question:

Might someone else have proposed the path, had Kennan not done so? Probably, in due course, but it’s hard to think of anyone else at the time who could have charted it with greater authority, with such eloquence, or within so grand a strategic framework.

Gaddis identifies Kennan’s writing skill as a keystone of his enduring legacy.

Not the least of the reasons Kennan succeeded as a strategist and a historian is that he used words well. There was passion, luminosity, vigor, and originality in almost all of his prose, so much so that its vividness at times obscured the meanings he meant for it to convey. Had it not been for that–had Kennan written as most other Foreign Service officers did–the world might never have heard of him, and his readers would not have retained the phrases, sentences, and sometimes whole paragraphs he so indelibly imprinted upon them.

Gaddis concludes that Kennan is, ultimately, best understood as a teacher.

Might that be said of each of these magnificent communicators?

The Power of Words | Havel, Hitchens & Kennan