Edmund Morris was best known as the author of an acclaimed triptych on Theodore Roosevelt. He’s one of the best of the notable group of popular historians who rose to fame in the 1970s and 1980s, continuing to the present day. As academe retreats into insularity, gifted writers such as Morris and David McCullough have brought history and biography to life for millions of Americans.

Morris’s decision to engage the life and legacy of Thomas Alva Edison was inspired. His deep study of Theodore Roosevelt positioned him well both to comprehend the significance of Edison and do the granular work to bring an increasingly distant figure to life.

Morris as Literary Biographer

As with TR, Edison’s life and work is singular and of a piece with his own time. Morris also demonstrates how strikingly relevant many aspects of their era is to our own. The transformational changes in technology, culture, and politics now underway are no more profound than those of a century ago. One could argue that the people of that time faced greater challenges.

His debut biography, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, is memorable for the match of Roosevelt’s larger-than-life early years with Morris’s literary sensibility. His subsequent works have shown greater and lesser success in his attempts to create, in Roosevelt’s words, history as literature.

Morris struggled with the limitations of the biographical genre in his authorized biography of President Reagan, Dutch. It’s a commonplace that the decisions of the non-fiction writer, adhering closely to the facts, may nonetheless depart from ultimate understanding or truth. Unable to get hold of Reagan as a political and cultural figure, Morris inserted himself as a fictional narrator, commenting on real-life events. The result was disappointing if not tragic; he was the late president’s authorized biographer, accorded rare access to the administration and its papers.

Edison’s ‘Rosebud’ Moment

In Edison, Morris faced the task of introducing the life and times of a figure whose accomplishments literally transformed the reality of life for his nation and the entire planet. The inventor emerges as not an entirely appealing personality. His legendary capacity for concentration and extended work was accompanied by strained personal and professional relationships. Edison was a great inventor by any reckoning. He was also remote and callous.

Morris reverses the chronology of Edison’s life. He opens with his subject’s death. This enables him to establish Edison’s significance and recognition by his contemporaries. Morris then moves backwards, dividing the life of the “Wizard of Menlo Park” by the subjects of his work.

It’s as if Thomas Alva Edison, phenomenon, is a great tree that Morris prunes and finally cuts to its core, its roots. The “Rosebud” moment, in Morris’s rendering, is Edison’s childhood loss of hearing. This is at once poignant—Edison’s inventions including breakthroughs in the transmission and recording of sound—and explanatory of the separation that was a foundation of his professional achievements and personal limitations.

Edison is meticulously researched and beautifully written. The book itself is well designed and formatted, with apt illustrations. It will likely not be regarded as highly as Morris’s work on Roosevelt. That may be an unapproachable standard. Nonetheless, it’s a brilliant introduction to an American original and his world.

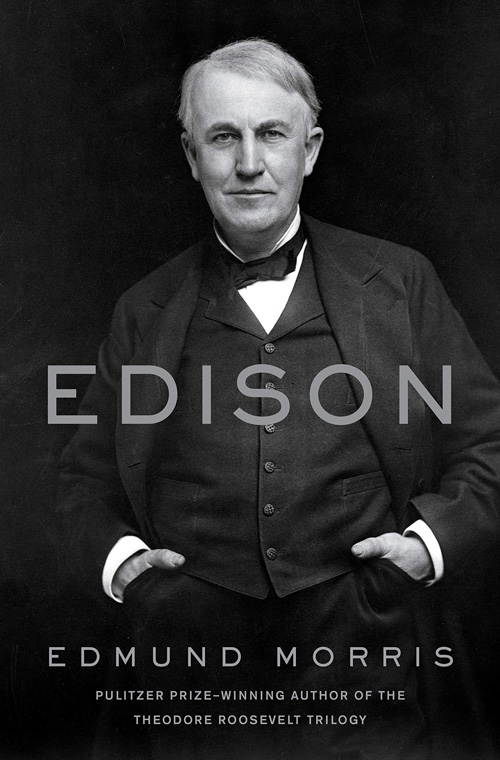

Edmund Morris | Edison