Monday, October 14, 1912. Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Autumn crispness was slipping in. Another demanding day dissolved into dusk, amid one of the most raucous, hard-fought, and consequential presidential campaigns in American history.

That evening, former president Theodore Roosevelt would take the cause of his breakaway third party to the people in yet another speech, in yet another auditorium.

Neither TR, nor anyone else, had any reason to anticipate the extraordinary events that were about to unfold.

No one, that is, other than an armed gunman, lurking in the lengthening shadows.

Roosevelt’s Moment of Truth

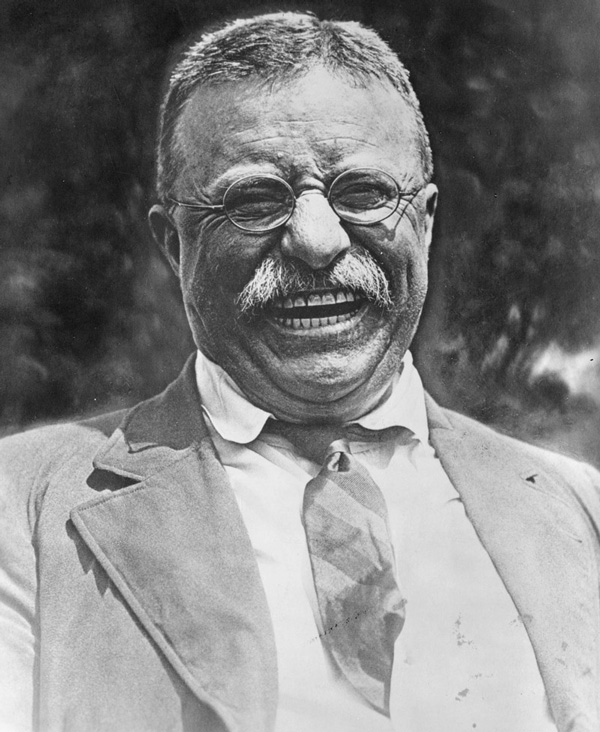

Fortified by a brief rest, Colonel Roosevelt, as he preferred to be called, emerged from the Gilpatrick Hotel. He took his seat in a waiting, open car. Acknowledging the cheers of a nearby throng, he rose to his feet, turned, tipped his hat.

Amid the indistinct crush of another campaign crowd, a deranged man with a pistol thrust himself forward…. In motion, at point-blank range, he fired a single shot straight into Roosevelt’s chest.

TR collapsed into the back seat…. Pandemonium gripped the scene….

Making History in Real Time

As recounted in Theodore Roosevelt on Leadership, Roosevelt remained preternaturally calm amid the chaos. He chose to comport himself as the indomitable Bull Moose.

Pulling himself together, he spit into a handkerchief. Detecting no blood, he declared himself unlikely to die from his wound. Ignoring the sensible advice of others present, TR directed that he be driven to his speech venue.

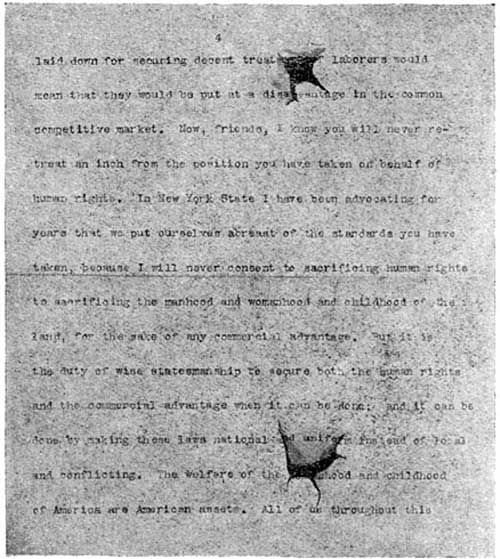

Without the benefit of a microphone, Roosevelt spoke for well over an hour. Reading from pages torn by the bullet’s path, TR presented one of the most memorable speeches of American history:

And now, friends, I want to take advantage of this incident and say a word of solemn warning to my fellow countrymen. First of all, I want to say this about myself: I have altogether too important things to think of to feel any concern over my own death; and I cannot speak to you insincerely within five minutes of being shot….I always felt that a private was to be excused for feeling at times some pangs of anxiety about his personal safety, but I cannot understand a man fit to be a colonel who can pay any heed to his personal safety when he is occupied as he ought to be occupied with the absorbing desire to do his duty.

After the speech was completed, he was taken by train to Chicago. Characteristically, he insisted on walking on his diminished power, rather than being rolled on a gurney into the hospital.

The New York Times observed: “Mr. Roosevelt showed the indomitable courage that is ingrained in his being. It was rash… an act of hardihood… even an act of folly, and the judgment of the country will be that it was magnificent.”

Virtue Aforethought

Roosevelt’s reactions in this crisis were unusual, to say the least. Can you imagine any public figures handling themselves in such a way today?

Where does such courage come from? How can it be encouraged and celebrated and nurtured?

TR pointed toward an indispensable element: forethought.

In the law there’s a concept called malice aforethought. It relates to the premeditation required as an element of certain crimes. Actions such as TR’s point to a corresponding notion, one that might be called virtue aforethought.

Roosevelt could not have known when he would face a situation such as that in Milwaukee. He well knew it was a possibility at any time. He had courted danger and death in various ways throughout his methodically eventful life.

As part of his decision to overcome fear, to transform himself into a person of manifest, serviceable courage, he doubtless had prepared for many scenarios. This may have been underscored by his time in the military and in law enforcement, where such training is required.

TR constantly examined and evaluated the courage and contributions of other leaders, including from history. He was on a first-name basis with many of them, after a fashion. In turn, that helped him think of the future generations, whom he addressed in every way he could. His children would laugh about his correspondence with them, recognizing “posterity letters.” No matter how or to whom they were addressed, they were intended for a wider audience.

When his own moment of truth arose–a moment in which his actions would reveal his ultimate truth—TR was ready.

Are You Prepared for Your Moment of Truth?

Roosevelt arguably dedicated much of his life aiming for heroism for those few moments, the “crowded hours” in which his fundamental truth would be summoned. Armed with forethought, he met the high standards of the historic leaders he analyzed and emulated.

What about you? Are you prepared for your moment of truth?

Hopefully it will not be a life-and-death matter. Nonetheless, there may be hinge moments in your life, dividing all that comes after from all that came before. Perhaps it’s recognizing an opportunity to pivot in your career to an unanticipated path that is consistent with your aspirations—perhaps disruptive of years of your own and others’ understandings and expectations.

Perhaps it will arise when you’re asked to do something in your work that’s inconsistent with your moral values.

Perhaps it’s being ready when someone you love steps forward with an unforeseen need at an inconvenient moment, when there’s no time for reflection. A pause, a glance, a grimace, a smile or a smirk, the smallest thing may change everything.

All moments in life are not alike—far from it. There are certain moments that are truly defining… moments of truth.

Are you preparing for yours? Would you be prepared if you faced such a decision on this very day? Would you be able to act with the speed of instinct, honed from forethought?

Are You Prepared for Your Moment of Truth?