Lawyers as Architects of the American Nation

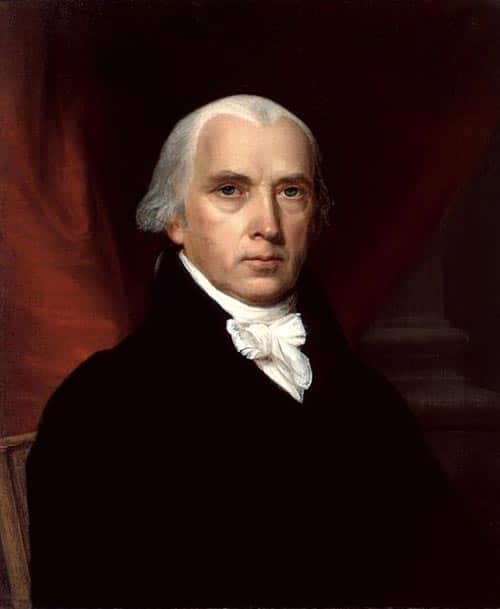

We pride ourselves on being a nation conceived and constructed on the rule of law. So it was that lawyers were midwives of our Constitution. As many as 34 of the 55 signers of the Constitution in Philadelphia were lawyers. James Madison, generally accorded honors as the driving force behind the constitutional vision, was a lawyer, as were Thomas Jefferson and John Adams.

The revered observer of American life in the early nineteenth century, Alexis de Tocqueville, himself a lawyer and an aristocrat, discerned the central role played by attorneys in the new nation:

In America there are no nobles or men of letters, and the people is apt to mistrust the wealthy; lawyers consequently form the highest political class, and the most cultivated circle of society. They have therefore nothing to gain by innovation, which adds a conservative interest to their natural taste for public order. If I were asked where I place the American aristocracy, I should reply without hesitation that it is not composed of the rich, who are united together by no common tie, but that it occupies the judicial bench and the bar.

Tocqueville elaborated:

The special information which lawyers derive from their studies ensures them a separate station in society, and they constitute a sort of privileged body in the scale of intelligence. This notion of their superiority perpetually recurs to them in the practice of their profession: they are the masters of a science which is necessary, but which is not very generally known; they serve as arbiters between the citizens; and the habit of directing the blind passions of parties in litigation to their purpose inspires them with a certain contempt for the judgment of the multitude. To this it may be added that they naturally constitute a body, not by any previous understanding, or by an agreement which directs them to a common end; but the analogy of their studies and the uniformity of their proceedings connect their minds together, as much as a common interest could combine their endeavors.

A portion of the tastes and of the habits of the aristocracy may consequently be discovered in the characters of men in the profession of the law. They participate in the same instinctive love of order and of formalities; and they entertain the same repugnance to the actions of the multitude, and the same secret contempt of the government of the people. I do not mean to say that the natural propensities of lawyers are sufficiently strong to sway them irresistibly; for they, like most other men, are governed by their private interests and the advantages of the moment.

Lincoln: Ideal of Lawyer as Leader

Abraham Lincoln was a renowned corporate lawyer, serving the powerful railroad interests. In the decades following his martyrdom, many revered him as representing the realizable ideal of the lawyer as leader.

In addition to critical thinking and argumentation skills, Lincoln stood for “disinterested’ service. This referred to service beyond self-interest, indeed to service to the public itself.

Such an ideal, by definition, will not always be achieved. Amid the financial, economic, cultural and political turmoil of the turn of the 20th century, many observers, including Louis Brandeis, concluded that the profession was losing much popular respect. It is perhaps not surprising that Theodore Roosevelt determined that he could not place the great corporate lawyer, Elihu Root, as his presidential successor. Root, Roosevelt believed, would be unable to overcome the hurdle of public opinion of Wall Street lawyers.

Whither the Lawyer-Statesman Ideal?

Is the ideal of the lawyer-statesman dead?

Anthony Kronman, a professor at Yale Law School, argues that it is–or, at the least, it’s out-of-sync with our time—in his useful book, The Lost Lawyer: Failing Ideals of the Legal Profession.

Kronman’s book is nearly three decades old. Another systematic look came two decades ago, from U.S. District Court Judge Patrick Schiltz, writing in the Vanderbilt Law Review.

Ben W. Heineman, Jr. offers another view in a concise, well-written article, “Lawyers as Leaders,” a 2006 lecture subsequently published in the Yale Law Journal. Heineman, who has combined law, business and public service in a distinguished career, argues that “graduates of law schools should aspire not just to be wise counselors but wise leaders; not just to dispense ‘practical wisdom’ but to be ‘practical visionaries’; not just to have positions where they advise, but where they decide.”

Most tellingly from a leadership perspective, Heineman declares: “We need lawyers who can create and build, not just criticize and deconstruct.”

Lawyers as Leaders in 21st Century USA

The issue of lawyers as leaders is now crystallized—fairly or not—in the saga of Jeffrey Kindler, an ousted CEO of Pfizer. The apparent consensus narrative is that Kindler was effective in private practice, and later as an in-house counsel, but faltered conspicuously in the chief executive role.

Without placing undue reliance on details from press reports, one can nonetheless recognize far-reaching issues in the Kindler circumstances. Are lawyers well-positioned for larger leadership roles? To the extent they are, is that a result of legal training and experience—or in spite of it? How are lawyers most effectively managed and guided in their leadership development and career transitions?

What about lawyers as leaders in other settings? In what situations do they tend to be most effective? Who are exemplars whose real-time experiences can be instructive for others?

The legal profession itself is in the midst of historic change. The disintermediation that has unleashed innovation in various industries and sectors is now breaking through the walls of the professions. How will lawyers respond? What new leadership opportunities are emerging? How are law firms and individual attorneys envisioning the future?

How are law firms and attorneys responding to the empowerment of individuals and institutions in the Information Age? In a time when corporations are consciously seeking to serve stakeholders beyond their shareholders, how do lawyers view their own representative roles and obligations in serving corporate clients? Are lawyers’ conceptions of the universe of stakeholders they’re serving also expanding? If so, how?

How are law firms and lawyers entering the new world of social engagement and transparency? How are expertise and authority understood and earned? How is value created and measured? What can law firms and lawyers learn from the disintermediation of other sectors? What aspects, if any, are unique to the legal profession?

These and other questions and challenges are arising at a time when leadership is recognized as desperately needed in all sectors. The sheer number of lawyers in the United States—according to the American Bar Association, over a million—suggests that there is immense potential for lawyers to serve more stakeholders, more effectively, and in new ways.

Lawyers as Leaders in 21st Century USA