It’s currently fashionable to diminish or dismiss the part played by individual leaders. Nonetheless, there are a few leaders whose actions and visions are decisive by any reckoning. Things would have been demonstrably different but for their service. Their legacies reach far into the future.

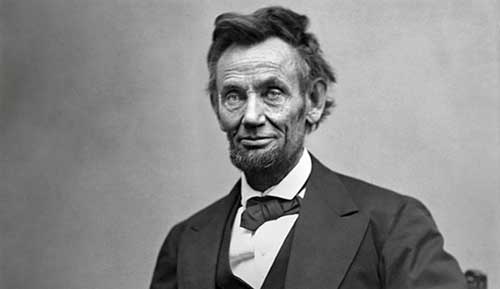

Abraham Lincoln is such a leader. His incomparable example inspired others, ranging from Leo Tolstoy to Theodore Roosevelt to Martin Luther King, Jr. to countless millions around the world today–and into the future.

Lincoln’s death in April 1865 marks a hinge of fate. His martyrdom was sealed by its timing: mere days after the unconditional surrender of the Confederacy.

If Lincoln led the nation to victory in war, he was taken before he could lead the nation in peace. We mourn the tragic denouement of the succeeding years: the failed Reconstruction of the South, the collapse of national politics amid recrimination and venality.

Had Lincoln lived, we can believe that he would have healed the wounds as no one else could. His second inaugural address from March 1865 stands as elegiac testament.

There’s another, very tough truth that is not generally dwelt upon. Lincoln’s vision for the future was betrayed in part by his own misjudgment.

For all his greatness, Lincoln committed a leadership error of the first magnitude. It would have reverberations from 1865 to this very day.

Lincoln Leadership Failure | Succession Planning

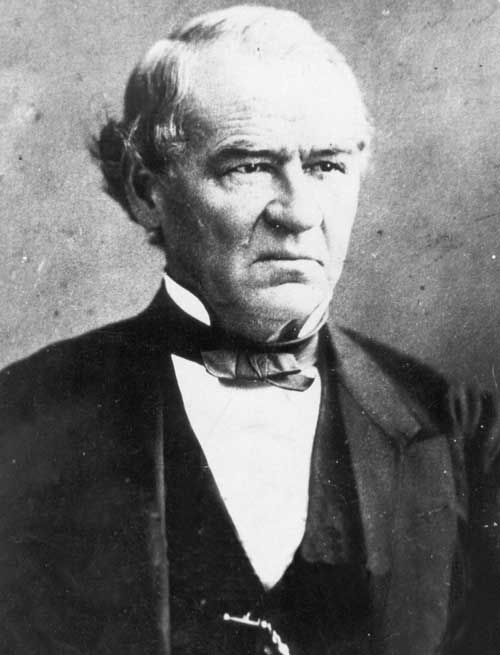

Lincoln’s error was the selection of Andrew Johnson as his vice president.

To be sure, Johnson on the ticket doubtless furthered some electoral goals amid the unsettled politics of the 1864 election.

Nonetheless, most historians agree that it was a disastrous decision.

Many leadership and management decisions cannot reasonably be evaluated without the benefit of hindsight. Not so the selection of Andrew Johnson. He was, by any reckoning, universally regarded as ill-suited for the demands of the presidency in his own time.

Dissipated, self-indulgent, dull-witted, President Andrew Johnson was the titular head of an administration that was a disaster. His signal accomplishment—if it can be seen as such—was narrowly averting impeachment. After Johnson’s sole term in the presidency, the balance of power shifted from the executive to the legislative branch. It would not return toward the executive until the turn of the twentieth century.

Lincoln’s great goals for the peace would have required leadership as skilled as the Great Emancipator’s war leadership. Lincoln’s own, unlikely effectiveness as a warlord was an ideal preparation for wending cannily through the snares of the national project of reconciliation and reconstruction.

In the hands of his successor, such noble visions collapsed in ruins.

Lincoln Not Alone

To be sure, Lincoln is far from alone as a high-position leader neglecting to attend to succession.

John Kennedy faced skeptical questioning relating to his selection of Lyndon Johnson as his vice president in 1960. Kennedy chose to overlook such concerns. The electoral math was surely decisive: without holding Texas in the Democratic column, it was likely impossible for Kennedy to prevail in the general election.

Jacqueline Kennedy reported that her husband feared a Johnson succession. Yet, given Kennedy’s relative youth—he was 43 when he was inaugurated in 1960—he and others saw that as a low-probability possibility.

Some of William McKinley’s closest aides openly fretted that his unconventional vice president, Theodore Roosevelt, might become president by an assassin’s bullet.

Franklin Roosevelt selected an unknown and ill-prepared Harry S Truman in 1944. FDR hardly spoke to his vice president. After Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, Truman was confronted with a range of existential issues for which he had not been briefe—including the development of the atomic bomb.

That some of these successions worked out well owed little to the decisions of the principals.

What About You?

Historical examples such as Lincoln’s are useful, because the issues at hand apply in many settings. The factors surrounding Lincoln’s succession planning in the nineteenth century are basically unchanged in the twenty-first century.

In the business and not-for-profit sectors, one can find a variety of approaches to succession planning.

At Apple, Steve Jobs’ many accomplishments include the grooming of Tim Cook.

At the U.S. Supreme Court, William Rehnquist exhibited shrewdness in his cultivation of John Roberts for the position of chief justice of the United States.

Are you planning your succession in your various roles? These could range from family to community to business.

Are you fulfilling your fiduciary responsibilities as a board member for enterprises? Are you pressing questions of succession even if they make a CEO uneasy?

It’s not enough to aim to serve future generations through one’s daily work. It’s also necessary to attend to the uncomfortable but necessary task of planning for the succession that could occur any hour, any day.

Lincoln Leadership Failure | Succession Planning