The mantra is that every day should be Earth Day.

We’ve all become more attuned to the ways in which all of our actions—individually and collectively—can create environmental costs.

In the nature of things, we also have more opportunities to serve and lead as environmental stewards.

21st century environmental leadership is emerging in distinctive ways from its 20th century antecedents.

10 Trends in 21st Century Environmental Leadership

1. International Affairs Are Pushing Environment-Energy Issues Front-and-Center. For many years, environmental issues have been discussed as national security issues. In the United States this occurs, in part, because of our history of political support for spending in defense-related fields (thus the linkage of domestic programs such as highways, education, etc. to national defense). Suddenly, this notion has far more weight.

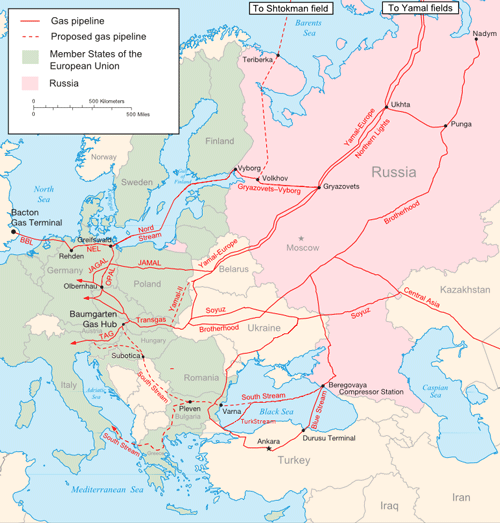

The breathtaking reliance of Germany and other European nations on Russian oil and gas is a central strand in the tangled statecraft relating to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022. At the same time, urgent climate disruption warnings continue, and the capacity for effective international efforts is brought into question by the apparent rise of regional blocs and new alliances. The post-1945 world order is in transition. One of the great questions ahead is how national governments and international institutions can achieve the unprecedented level of cooperation and transparency required for continued environmental progress—at the same time as national and great power competition in various sectors is heightening.

Incorporating environmental considerations into international statecraft is an urgent priority.

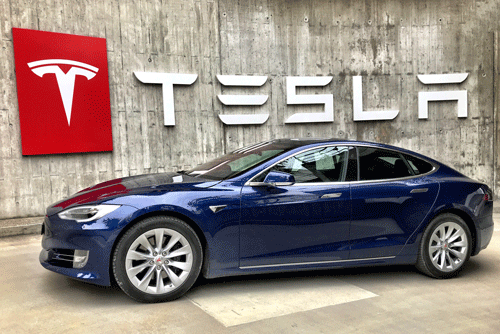

The Russia-Ukraine War is bringing a number of elements into sharp relief. For example, some politicians’ attempts to demonize the oil-and-gas industry in the name of the environment have been exposed as shortsighted (petroleum products will continue to have various uses; in the near term, oil and gas may be required as a backup or baseline energy source during the transition to electrification) and counterproductive (limiting US production and prompting politicians to seek supply from environmentally and strategically unreliable nations such as Venezuela). There will also be environmental, strategic, and supply aspects to producing, distributing, and using critical minerals for the transition, such as lithium for electric vehicle batteries.

The United States has enacted and is now implementing the Inflation Reduction Act. The name notwithstanding, the new statute includes sweeping provisions intended to speed decarbonization in the remainder of this decadea and beyond.

Meanwhile, far-reaching, new challenges are rising. Among them is the discovery of microplastics in the food chain across the world—in human blood as well as the stomachs of deep-sea fish—prompting overdue, heightened scrutiny of ocean protection.

2. Traditional Environmental Challenges Remain Urgent. The United States and other developed nations have made extraordinary progress in reducing and cleaning up pollution that is visible (think smog in Los Angeles, rivers on fire in Ohio). That said, traditional tasks remain far from complete. Pipelines, leaks, and chemical spills sporadically assault the environment, including in precious coastal ecosystems. Water infrastructure is aging in many areas, reflecting an out-of-sight-out-of-mind procrastination by political actors. China and other developing nations face extraordinary environmental and public health challenges. The distinctions between local, provincial, national, regional, and international issues continues to recede.

3. The Culture is Changing for the Better. The time is long past when environmental protection as an ideal is a matter of public controversy in the United States. There are outliers—but they are just that, outliers. Individuals, corporations, governments are searching for ways to serve more effectively, to engender innovation. The evolving culture aligns the self-interest of enterprises with the protection of the planet. On any given day, TriplePundit, Environmental Leader, GreenBiz, Grist, and other publications report breakthroughs and identify opportunities. The significance of this cannot be overstated. The culture change has various causes, including citizen action, political leadership, civil and criminal liability and enforcement, the support of Hollywood, increasing spiritual and religious linkages, and so on.

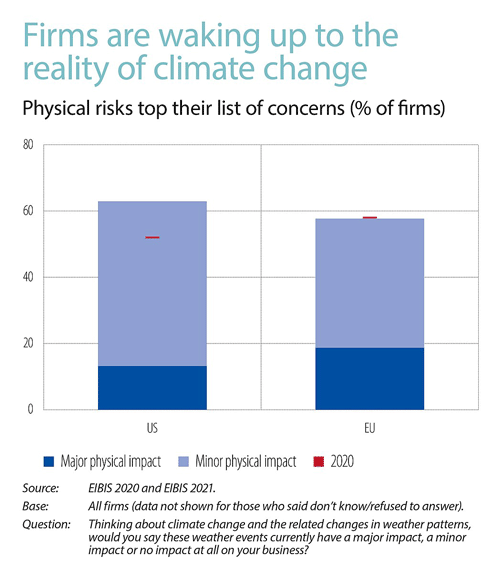

4. Finance is Supplementing Law as Key Driver of Change. The first phase of the modern environmental movement focused on statutory and regulatory change. Rising law enforcement sped the process of institutionalizing environmental consciousness. Large and then smaller companies changed course. The military and other government agencies—from the national to the state to the local level—have been increasingly brought into compliance.

Now, attention is turning to the financial sector. Green capital expenditures are rising remorselessly. The confluence of environmental concerns with social and governance issues (ESG) is increasingly built into bureaucratic organizations of all kinds. A notable landmark can be seen in the powerful 2022 proxy letter from the legendary Carl Icahn to McDonald’s management and shareholders focused on ESG performance and prospects.

5. Decarbonization Is Getting Real. The decline of American political leadership over the past generation is reflected in the historic failure to enact comprehensive climate disruption statutes or treaties. The Inflation Reduction Act (2022) provisions relating to clean energy are a signficant step forward.

Through an improvisational combination of regulation and private-sector financial practices, the transition from a carbon-reliant economy is underway. This is seen in a range of decarbonization efforts, including electric vehicle production and infrastructure; carbon removal in agriculture, industry, and the energy sector; carbon trading markets; insurance updates; and heightened transparency and disclosure. Innovation is flowering across many fields, such as regenerative architecture. Perhaps the single most significant change is the more favorable consideration of nuclear power as an element of future energy supplies, spurring prospective breakthroughs such as Generation IV reactors.

6. Cities Are an Emerging Force. One of the momentous changes in our time is the urbanization of the world. This presents momentous challenges. The mass movement from countryside to cities is accompanied by rising expectations for living standards, including motor vehicles, consumer goods, etc. As the OECD reports: “Cities account for more than 70% of global energy-related CO2 emissions and an estimated 50% of global waste, and are home to nearly half of the world’s population.” There are reasons for optimism. In an age of decentralization, cities are proving more politically adept and adaptive than national governments in many aspects. So, too, the potential of cities is being nurtured and harnessed in new ways, such as the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities initiative. Such efforts spur cascading after-effects, as various jurisdictions learn and adapt successful approaches.

7. Actionable Transparency Is Becoming Universal. In our time of Google Maps and universal access to smartphones, there is no corner of the earth that can be plundered in the dark, out of sight. Basic information, let loose in a world of rising environmental consciousness, is transformative. Groups such as the German-based Living Lakes Network deploy social media tools to bring attention to vulnerable ecosystems and provide a venue to focus advocacy on their behalf. Actionable transparency is also advanced by the ongoing adoption of recognized metrics and sustainability standards, increasingly included in investment reporting and decisions.

8. Risk Communication Is Rising in Significance. The capacity of citizens to hold government, corporate, and non-governmental organizations to account for their environmental performance is a vital question for American policy. General political polarization, exacerbated by social media, has resulted in an overarching lack of trust in authoritative institutions. The challenges were on display in real-time amid the global COVID pandemic. Risk communications in the environmental space are correspondingly in need of innovation.

9. Environmental Politics Have Become a Lagging Indicator. In the 20th century, environmental politics were the leading edge of change. In the 21st century, environmental politics have receded to become a lagging indicator. In one sense, that’s to be anticipated—politics should reflect and catalyze change, as has occurred in cultural attitudes toward the environment. In a larger sense, it’s become problematic.

In the United States, environmental politics—at the national level—remains troubled. A generation has passed since the last major federal statutory overhaul, the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. The precedent-setting Montreal Protocol was ratified in 1988. Various partisan configurations of the executive and legislative branches in Washington have each, in their turn, failed to reverse this baleful trend.

It’s not as if change isn’t needed. The landmark national statutes are based on the politics of the 1970s and 1980s—and on thinking from even more distant times. Scientific policy issues require review and reform. Such lapses have consequences. Regulatory attention and resources are arguably misallocated by the EPA, particularly with respect to toxic and hazardous substances. A multiplicity of other federal agencies, congressional committees and subcommittees, and state agencies are, all too often, uncoordinated and unproductive in their operation.

History suggests that presidential leadership is necessary. The lapses in Washington arise in part from the special interest domination and dysfunction hobbling the entire national government. Nonetheless, reforms of the environmental-energy space can begin now. The statutes can be updated and consolidated, as can the operating agencies and their congressional overseers. International issues merit much more institutional attention than at the time the EPA was founded a half-century ago. Domestically, consistent with the decentralizing trends of the digital age, the federal government might well rationalize its relations with cities and states, setting standards and ensuring enforcement, while relinquishing other functions. Overall, great benefits could be achieved through agreed metrics of accountability, relentless simplification of process, and an innovation ethos.

10. Generational, Demographic Change Hold Promise. As reported in an important Pew survey, there are measurable differences in viewpoints on environmental matters based on generational cohort and other demographic factors. There’s a continuing challenge of expanding environmental values beyond the upper-middle-class precincts where they hold greatest sway. This is reflected in the rising concerns about unanticipated, vexing ‘Green Jim Crow’ effects from the intersection of land use and environmental regulations. It’s prompting an overdue recognition of the needs of underserved communities, including, perhaps most important, how to ensure participation in decision-making.

Perhaps most positive is the likelihood that rising generations will combine urgent demands for environmental results with openness to renovating institutions and reviewing their operating assumptions.

10 Trends in 21st Century Environmental Leadership

[…] the twenty-first century, what trends in the environmental forces (social, economic, technological, competitive, and regulatory) (a) work for and (b) work against […]